Using the guide and getting started

The guide is structured so that it can be used either in full or just specific sections can be accessed for guidance when the particular task covered by that section is being addressed by course teams and their leaders.

Before looking at the Section on ‘The six ‘keys’ in flipping the curriculum’ or the Section ‘Making it happen’ the Fellowship participants repeatedly urged that it is important to:

- Confirm that everyone involved has a shared understanding of key terms;

- Take into account the extensive work already undertaken in this area;

- Help people to see where the focus of this guide fits into the bigger Learning and Teaching quality and standards picture by ensuring everyone is clear on:

- The overall HE L&T Quality and Standards Framework within which the guide fits;

- The nature and use of the graduate capability framework validated during the Fellowship.

- The importance of developing graduates who are work ready plus.

To help your team address these preparatory issues in each area for each issue participants have identified the key question(s) your team might seek to answer and they have then provided suggestions on how these questions might best be addressed. Whenever relevant, links to relevant resources produced by others already working on the area concerned are given.

Key questions to ask

- How do we define key terms like ‘standard’, ‘quality’, ‘learning’, ‘assessment’, ‘strategy’ and ‘evaluation’?

- Have we all come to a shared definition of each of these key concepts?

- Does our institution have a glossary of such terms that all staff use?

Suggestions from the Fellowship participants

It is important that, from the outset, everyone has a shared understanding of key terms. If this step is not taken it is possible to find out later on that people have been talking at cross-purposes.

It is useful, therefore, to come to agreement on the meaning of terms like the following at the outset of any change initiatives in the area (indicative definitions are provided but it is important that staff come to consensus on the meaning of terms like these themselves);

- Standard – a level of achievement with clear criteria, indicators and means of testing.

- Quality – fitness for purpose/fitness of purpose and performance to an agreed standard.

- Learning – a demonstrably positive improvement in the capabilities and competencies that count.

- Assessment – gathering evidence about the current levels of capability and competency of students using valid (fit-for-purpose) tasks.

- Strategy – linking relevant, desirable and clear ends to the most feasible means necessary to achieve them.

- Evaluation – making judgements of worth about the quality of inputs and outcomes (including the evidence gathered during assessment).

In this guide the term ‘Program’ is used to describe the overall course of study that leads to a degree, diploma or other higher education qualification. The term ‘unit of study’ is used to describe one of the subjects that make up the program. We are aware that in some jurisdictions different definitions of the same terms are used. For example in some higher education systems ‘course’ refers to the overall program (degree, diploma or certificate) whereas in other jurisdictions ‘course’ refers only to an individual subject or unit of study.

In particular clarify what you all mean by the concept of ‘learning outcomes’

In using this guide it is especially important to come to your own agreed definition of what the term ‘learning outcome’ means. Below is a definition discussed and endorsed during the Fellowship workshops:

‘The capabilities and competencies students are expected to demonstrate they have developed to a required standard by the end of a program or unit of study.

They include personal, interpersonal and cognitive capabilities as well as the key knowledge and skills necessary for effective early career performance and societal participation’.

(This definition aligns with the validated successful graduate capability framework discussed in Section 3.2 below)

Key questions to ask

- Are we all clear on the extensive work already undertaken on this area?

- Is there some form of clearing-house for all staff to access that can help make the use of this work easy to use?

Suggestions from Fellowship participants

Extensive work has been undertaken in earlier Office for Learning and Teaching (OLT)/Australian Learning and Teaching Council (ALTC) projects and fellowships on assuring the quality of assessment in Australian higher education, with particular attention being given to assuring the fitness for purpose of assessment, assessment integrity and the use of assessment for learning as well as of learning.

One group of projects has given focus to establishing guiding principles for enhancing assessment practices, the effective use of assessment to improve learning during and after courses and achieving better alignment between assessment, learning and teaching, along with the inclusion of additional dimensions like global citizenship in assessment and the optimum ways in which to assess graduate attributes. A second group of projects has concentrated on cross-institutional mechanisms for assuring reliable grading, including a range of moderation schemes, electronic marking and feedback systems, and strategies for assuring academic integrity. A third cluster has developed and tested new assessment tools. A fourth group has explored capacity development for staff and students on assessment.

Helpful stocktakes of such work include:

Boud, D (2010): Assessment futures website at: http://www.uts.edu.au/research-and-teaching/teaching-and-learning/assessment-futures/overview

Calvin Smith et al: Graduate outcomes – a resource bank from work-integrated learning, graduate capabilities and career development projects, ALTC extension Project.

Freeman, M & Ewan, C (2014): Assuring learning outcomes and standards: good practice report, OLT, Sydney

Some relevant websites

- Romy Lawson’s Assuring Learning website

- David Boud’s Assessment Futures website

- Geoff Crisp’s Transforming Assessment website

- Nicky Lee’s Capstone Curriculum website

Towards a National Peer Review of Assessment Clearing House

This is currently under development by Education Services Australia and provides searchable access and support to each of the key areas covered in the guide to follow. For updated details contact Sarah Booth at: sara.booth@utas.edu.au

Key questions to ask

- Are we all clear on where a focus on program learning outcomes fits into the full picture of what is necessary to assure the quality and standards of Learning and Teaching in higher education?

- Do we have an agreed, validated, comprehensive picture of what a professional and graduate capability framework for our institution should cover?

- What distinguishes a work ready plus graduate?

Suggestions from Fellowship participants

The workshop participants recommended that any work in this area starts by sharing an overall quality and standards framework which shows how everything fits together in higher education learning and teaching (L&T) and then by identifying where the focus of this guide fits into this bigger picture.

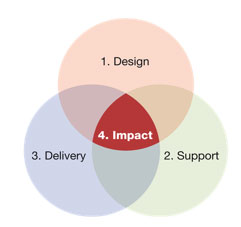

The L&T Quality and Standards framework outlined in Figure One (below) was tested and endorsed as being relevant at the Fellowship workshops. It has been developed from a range of research on what engages and retains higher education students in productive learning and commended in an external quality audit. It is now being used in a range of HEIs within and beyond Australian to achieve successful quality assurance and improvement for L&T.

Quality and Standards Framework for Learning & Teaching in Higher Education

1. Course design standards

|

2. Support standards

|

3. Delivery standards

|

4. Impact - Academic learning standards

|

|

Continuous process of Planning, Implementation, Review and Improvement (PIRI), against clear KPIs and standards for each of the above based on student feedback and independent review |

Clear sequence of trained governance and management roles and accountabilities |

| Underpinning Quality Management System |

The framework has two components. The top half identifies what needs to be given focus when seeking to assure academic standards and the quality of learning, teaching and assessment. The lower half (the Underpinning Quality Management System) represents how a university can ensure that these standards are applied, tracked and improved consistently and effectively. It is the careful and consistent attention to both areas that provides for effective academic quality management, improvement and assurance. The top section of the framework is comprised of four interlocking domains, each with its own set of standards and quality checkpoints:

- Course design

- Learning support

- Delivery

- Learning outcomes and assessment (impact).

Whereas domains one and two in Figure 1 (above) are concerned with assuring the quality and standard of inputs, domains three and four focus more on the quality of outcomes.

It was agreed during the Fellowship meetings and workshops, that the key test of Learning and Teaching quality and standards resides in the fourth domain (achieving a demonstrably positive impact on the capabilities of graduates). And it is this which is the focus of this guide.

The framework distinguishes between domain 3 - ‘delivery’ (what teachers do) and domain 4 – ‘learning’ (what learners do). In this context, 'learning' concerns the extent to which students' capabilities and competencies have developed in a desirable (professionally and socially relevant) direction over the course of their studies.

Because of this, giving focus to validating course-level learning outcomes (domain 4) using a suite of agreed external and institutional reference points is seen by the Fellowship participants a key first step in course development. Only when this is done is it then necessary to ‘map backwards’ from these validated level 4 outcomes to ensure that they are progressively developed in a staged way in units of study and assessed validly and reliably through engaging, fit for purpose, learning experiences and resources (domain 1) whilst concurrently ensuring that there is aligned support for this process (domain 2) and consistent delivery by capable staff (domain 3). In using such a framework, the university aims, therefore, to ensure that design, support and delivery decisions are not only relevant but also aligned, mutually reinforcing, outcomes focused and evidence based.

Every component of the framework in Figure 1 (above) comprises those empirically determined quality checkpoints known to optimise the retention and engagement of students in productive learning. When using the framework, specific focus is given to ensuring that every staff member - whether academic or professional - can see what contribution their role makes in helping to retain and engage students in productive learning and that whenever they deliver this role effectively this is acknowledged.

What matters to students is the combined and consistent quality of all four domains in Figure 1 (above) (i.e. the total university experience) and it is the extent to which the validated standards in all four areas are consistently and effectively delivered and monitored that determines the quality of graduates.

When new programs are designed using the framework, concurrent attention needs, therefore, to be given to assuring the standards in all four domains. For example, if a course design includes interactive, online learning and downloads requiring high band-width, the capacity of the university's ICT support systems and infrastructure to deliver this effectively must be confirmed before the course is approved. Similarly, if the course requires staff with a particular profile, their availability to deliver the course must be confirmed before the course is approved. This is why the circles in Figure 1 (above) are shown to overlap.

As noted earlier, much excellent work has been undertaken on levels 1-3 of this quality and standards framework (learning design, assessment for learning, support and delivery and assuring reliable assessment in higher education) in earlier OLT projects and other research and development initiatives within and beyond Australia.

However, less specific attention has been given to Level 4 – to making sure that, in the first place, the program learning outcomes and the capabilities of the graduates we are seeking to develop are validated (confirmed through evidence-based peer review) as being what is needed not just for today but for tomorrow. Undertaking this work to assure the fitness of purpose of program level outcomes (that is their relevance, desirability and feasibility) and their aligned assessment is very important as it is from universities that the largest number of political leaders, inventors and social and economic entrepreneurs come. And it is, therefore, to this level 4 component which sits at the heart of the quality and standards framework in Figure 1 (above) that the guide gives particular focus.

Participants also suggested that closer attention be given to identifying and confirming the sorts of assessment tasks that are most suited to measuring these validated program level outcomes. So particular attention is also given in the guide to this aspect of the design dimension of the framework, with a wide range of examples of ‘powerful assessment’ identified during the workshops included and links to the detailed work in other projects provided.

Participants consistently noted that it is by looking at the assessment tasks used to test unit or program level outcomes that we can identify what capabilities and competencies are actually being developed in our higher education students.

It was widely agreed that there is a need, when seeking to formulate program level outcomes (the impact dimension in Figure One), program teams need a more comprehensive and validated picture of what graduate and professional capability entails. And it is to this issue that we now turn.

Right Program Outcomes

Key question to ask

- When formulating program level outcomes are we using an agreed, validated, comprehensive picture of what a professional and graduate capability framework for our institution should cover?

Suggestions from Fellowship participants

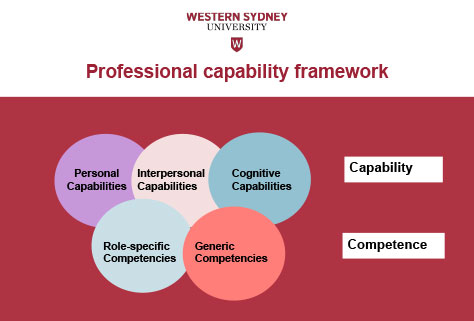

What was repeatedly emphasised during the workshops was the importance of program design and review teams using a comprehensive, validated professional and graduate capability framework to inform the way in which they gather information on what should be given focus in learning programs and in expressing the results.

Such a framework developed and validated in studies of successful early career graduates in nine professions and in a range of employer focus groups and surveys over the past decade was tested at the workshops and attracted particularly positive feedback. It was repeatedly noted that using such a framework and the validated set of subscales and items that make it up would considerably enhance the validity and comprehensiveness of the feedback now being sought from professional groups, employers, entrepreneurs and successful early career graduates.

The workshop participants also recommend its use as a way of enabling both staff and students to see how various unit and program level outcomes fit together in an integrated way. This, they said, would help overcome the tendency in some areas to produce long unlinked lists of outcomes to be achieved and unintegrated ‘modules’ of study. What was also noted was the importance of everyone distinguishing between key terms like ‘capability’ and ‘competence’.

Figure 2 outlines the validated framework endorsed at the workshops. Also included are the factor-analysed subscales that make up the dimensions of personal, interpersonal and cognitive capability. What was repeatedly noted in the feedback from participants from the workshops was how helpful this framework was in helping participants see the overall nature of professional and graduate capability and competence in operational terms and to see how it was the combination of all five dimensions in Figure 2 that was important for effective professional performance.

The studies of successful graduates, leaders and professionals that generated the framework and the capability sub-scales have repeatedly confirmed that one’s capability is most tested not when things are running smoothly but when something goes awry, when an unexpected event or opportunity arises or when one is confronted with a dilemma. It is then that the distinctive combination of personal, interpersonal and cognitive capabilities identified in these studies must come into play if the situation is to be successfully negotiated. This, as we shall see later in the guide, has important implications for what constitutes ‘powerful assessment’ in higher education.

The successful early career graduate studies held over the past decade have repeatedly shown that generic and role specific skills and knowledge (competencies) are necessary but are not sufficient for one to be identified as an effective professional practitioner by employers, clients or colleagues. It is the ability to remain calm, manage the uncertainty, listen with focus, actively engage others and diagnose in ‘messy’ situations that have both interlaced human and technical dimensions that is critical. It through this process of ‘reading and matching’ (Hunt, 1977) that we have found effective practitioners work out which particular combinations of their well-developed skills and knowledge base are most (and least) relevant to addressing each new situation.

Capability subscales

| Personal Capabilities | Interpersonal capabilities | Cognitive capabilities |

|

|

|

Make sure everyone is clear on the distinction between 'capability' and 'competence'

A brief distinction between capability and competence (which aligns with the 'five circle' framework in Figure 2 and the capability subscales above) is given in Scott (2013) :

‘It is important to distinguish between the terms 'capability' and 'competence', as they are often used interchangeably but incorrectly:

Whereas being competent is about delivery of specific tasks in relatively predictable circumstances, capability is more about responsiveness, creativity, contingent thinking and growth in relatively uncertain ones. What distinguishes the most effective (performers) ... is their capability - in particular their emotional intelligence ... and a distinctive, contingent capacity to work with and figure out what is going on in troubling situations, to determine which of the hundreds of problems and unexpected situations they encounter each week are worth attending to and which are not, and then the ability to identify and trace out the consequences of potentially relevant ways of responding to the ones they decide need to be addressed ...

While competencies are often fragmented into discrete parcels or lists, capability is a much more holistic, integrating, creative, multidimensional and fluid phenomenon. Whereas most conceptions of competence concentrate on assessing demonstrated behaviours and performance, capability is more about what is going on inside the person's head’ (Scott, Coates and Anderson 2008, 12).

And, as John Stephenson (1992: 1) concluded almost a quarter of a century ago, capability depends '... much more on our confidence that we can effectively use and develop our skills in complex and changing circumstances than on our mere possession of these skills'.

Use the factor-analysed items that make up the capability subscales to ensure feedback from key players is comprehensive and considered

Personal capabilities

Table 1 presents the scales and items developed to provide measurement of the domain of personal capability in the Scott, Coates & Anderson study (2008) and tested in subsequent studies, focus groups and workshops. This aspect of the practitioner’s capability is made up of three interlocked components: Self-awareness, Decisiveness and Commitment.

Table 1: Personal capability scales and items

| Scale | Item |

| Self-awareness | Deferring judgment and not jumping in too quickly to resolve a problem |

| Understanding my personal strengths and limitations | |

| Being willing to face and learn from my errors | |

| Bouncing back from adversity | |

| Maintaining a good work / life balance and keeping things in perspective | |

| Remaining calm under pressure or when things take an unexpected turn | |

| Decisiveness | Being willing to take a hard decision |

| Being confident to take calculated risks | |

| Tolerating ambiguity and uncertainty | |

| Being true to one's personal values and ethics | |

| Commitment | Having energy, passion and enthusiasm for my profession and role |

| Wanting to produce as good a job as possible | |

| Being willing to take responsibility for projects and how they turn out | |

| PA willingness to persevere when things are not working out as anticipated | |

| Pitching in and undertaking menial tasks when needed |

Interpersonal capabilities

Table 2 presents the scales and items developed to provide measurement of the practitioner’s interpersonal capabilities. This has been distinguished into two subscales: Influencing and Empathising.

Table 2: Interpersonal capability scales and items

| Scale | Item |

| Influencing | Influencing people's behaviour and decision in effective ways |

| Understanding how the different groups that make up my university operate and influence different situations | |

| Being able to work with senior staff within and beyond my organisation without being intimidated | |

| Motivating others to achieve positive outcomes | |

| Working constructively with people who are 'resistors' or are over-enthusiastic | |

| Being able to develop and use networks of colleagues to solve key workplace problems | |

| Giving and receiving constructive feedback to/from work colleagues and others | |

| Empathising | Empathising and working productively with people from a wide range of backgrounds |

| Listening to different points of view before coming to a decision | |

| The ability to empathise and work productively with people from a wide range of backgrounds | |

| Being able to develop and contribute positively to team-based programs | |

| Being transparent and honest in dealings with others |

Cognitive capabilities

Table 3 presents the scales and items developed to provide measurement of the domain of cognitive capability. This aspect of the practitioner’s capability is made up of attributes that fit into three interlocked subscales: Diagnosis, Strategy and Flexibility & Responsiveness.

Table 3: Cognitive capability scales and items

| Scale | Item |

| Diagnosis | Diagnosing the underlying causes of a problem and taking appropriate action to address it |

| Recognising how seemingly unconnected activities are linked | |

| Recognising patterns in a complex situation | |

| Being able to identify the core issue from a mass of detail in any situation | |

| Strategy | Seeing and then acting on an opportunity for a new direction |

| Tracing out and assessing the likely consequences of alternative courses of action | |

| Using previous experience to figure out what's going on when a current situation takes an unexpected turn | |

| Thinking creatively and laterally | |

| Having a clear, justified and achievable direction in my area of responsibility | |

| Seeing the best way to respond to a perplexing situation | |

| Setting and justifying priorities for my daily work | |

| Flexibility & Responsiveness | Adjusting a plan of action in response to problems that are identified during its implementation |

| Making sense of and learning from experience | |

| Knowing that there is never a fixed set of steps for solving workplace problems |

Take into account the results of studies of successful early career graduates and the feedback from employers when using this comprehensive framework

When the above framework, subscales and items are used to get feedback from successful early career graduates, employers, professional associations or other groups what is provided gives a more comprehensive, accessible and operational picture of what program level learning outcomes and assessment need to focus upon.

Table 4 identifies the highest ranking items when the results from studies in 9 professions (see references) are brought together and Table 5 shows the items rated greater than 4/5 on importance in a survey of 147 Western Sydney employers using the same framework and scales.

Table 4

Exemplar

|

Top ranking capabilities from studies of successful graduates in 9 professions (top 12/41 in rank order)

|

Table 5

Exemplar

|

Capabilities rated greater than 4/5 on importance by 147 Western Sydney employers Personal capabilities

Interpersonal capabilities

Cognitive capabilities

Generic skills & knowledge

|

What is noteworthy about the results is how important a particular set of personal, interpersonal and cognitive capabilities are; and how having high levels of relevant role specific and generic skills and knowledge (competencies) is necessary but not sufficient to be an effective practitioner. What emerges is the critical importance of ‘mindfulness’ and a capacity for diagnosis, creativity and contingent thinking.

These workshop participants said, highlights how important it is when we assess students and prepare them for professional practice to ensure that ‘authentic’, real-world, integrated, ‘powerful’ assessment tasks that directly measure the top rating capabilities for each profession in combination are used. Of particular interest in the workshops were the examples of how assessment tasks based on the real-world dilemmas of successful early career graduates. This, said participants, is because they reflect not only what professional practice is actually like but also because they provide a powerful and scalable way to test concurrently the key capabilities across all of the dimensions outlined in Tables 1-3. The hundreds of ‘powerful’ assessment tasks identified by participants in the Fellowship workshops show a wide range of options for how this can be done are discussed later in the guide and a searchable database of examples sorted by field of education is also available.

The Fellowship participants suggest that course design and review teams seek not only to use the above framework and items when seeking to validate (confirm the relevance and desirability of) program learning outcomes. They also suggest that they program teams consider using the capability framework and subscales in Figure Two to cluster them, thereby providing a more coherent and operational picture for students on what they need to concentrate upon in their learning and assessment.

“The Australia of the future has to be a nation that is agile, that is innovative, that is creative. We cannot be defensive, we cannot future-proof ourselves. We have to recognise that the disruption that we see driven by technology, … volatility and change is our friend if we are agile and smart enough to take advantage of it”.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull September 2015

Key question to ask

- What is a work ready plus graduate?

Suggestion from Fellowship participants

The workshop participants and key leaders interviewed during the Fellowship particularly liked the notion of developing graduates who are not only work ready for today (competent) but who are also work ready plus for tomorrow (capable). This is because, said participants, we need professionals who not only possess the relevant skills and knowledge to undertake set tasks in predictable circumstances but also the ‘higher order’ capabilities to manage both the human and technical challenges that arise at moments of uncertainty, when change is in the air, or when quite new, unexpected opportunities arise. It is, they said, at times like these that one’s professional capability is most tested, not when things are running smoothly or predictably. And it is our graduates who will play a central role in addressing the innovation agenda identified in the quote above from the Australian Prime Minister. Box One summarises four of the key attributes of work ready plus graduates which were identified, endorsed and discussed in the workshops.

|

Box One Work Ready Plus Graduates People who are not just work ready for today but work ready plus for tomorrow. The plus can include being:

|

In discussing the four work ready plus capabilities in Box One, it was emphasised that universities and colleges don’t just produce professional workers. As already noted, they produce our future leaders (the vast majority of the world’s political leaders and policy makers have been to a university or college); and they can develop people capable of creating their own enterprises and inventing the new sources of income we need for economic sustainability as old resource-based revenue sources dry up and ‘digital disruption’ rapidly reshapes business models and how people work. University graduates can also play a central role, said participants, in developing the breakthroughs necessary to manage environmental and economic sustainability and the solutions necessary to secure social and cultural sustainability and foster harmonious societies.

Supplementary resources and guidelines on graduate and professional capability

Graduate capabilities and employability

- EU report (2013) ‘The Employability of Higher Education Graduates: The Employers’ Perspective’ http://www.delta.tudelft.nl/uploads/pdf/employabilitystudy_final.pdf

- UNESCO report (2012) graduate employability in Asia

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002157/215706e.pdf - EMERGING consultancy (France) report on ‘ Global Employability Survey and University Ranking 2013 :Recruiters worldwide describe their “Ideal University“ Main results

- Graduate Careers Australia research http://www.graduatecareers.com.au/research/exploreourresearch/

- Beyond Graduation, Graduate Careers Australia. Higher Education Academy: Employability, UK, HEA.

- Yorke, M & Knight, P (2006): Embedding employability into the curriculum, UK, HEA. See for example pgs 8 & 15 where a set of key capabilities/skills associated with employability are identified and pgs 19 ff where a ‘capability envelope’ is discussed.

- Walsh, A & Kotzee, B (2010): Reconciling ‘graduateness’ and work-based learning, Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, Issue 4-1: pp 36-50.

Developing graduates who are work ready plus

- Fullan, M & Scott, G (2014): Education Plus, New Pedagogies for Deep Learning Partnership, Washington.

- Boyer, Ernest 1987): The undergraduate experience in America, Harper Collins, New York. See the discussion around pgs 283.

- Moline, K (2015): Myths of the near future, ABC, Future Tense 1 Oct 2015 at: http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/futuretense/myths-of-the-near-future/6888830 “ Smart phones now have a powerful and ongoing daily role in shaping and structuring our lives, but Katherine believes many of us take them for granted; and that it’s time to look anew at the way in which we use technology to shape the stories we tell about ourselves and others”. They are devices which are more than communication devices – “they curate and shape the narrative of our identity”.

- Professor Mark Dodgson , Director of the Technology and Innovation Management Centre at the University of Queensland Business School, Occam’s Razor, ABC RN 24th May 2014 ‘Universities contribute to explaining and solving the complex problems we face, socially, economically, and environmentally.…. The university should be less concerned with today’s business and more with tomorrow’s. When I speak to leaders of forward-thinking companies around the world they say the last thing they want is for universities to replicate what they do. They want universities to do the longer-term, more speculative work they don’t and can’t do themselves. The next time someone in business says universities need to do what the market demands, remind them of Henry Ford’s statement that if he’d listened to what his customers demanded, he’d have given them a faster horse ’.

- QAA (2012): Enterprise and entrepreneurship education, QAA, UK at: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/en/Publications/Documents/enterprise-entrepreneurship-guidance.pdf See Graduate outcomes for enterprise, entrepreneurship & invention pgs 16-21 (note the close links to the professional and graduate capability framework).

- Rosen, Larry D (2012): iDisorder: understanding our obsession with technology and overcoming its hold on us, Palgrave Macmillan, N.Y.

- Stephenson, J & Yorke, M (1998): Capability and quality in HE, Kogan Page, Oxon.

Studies of successful early career graduates

These are listed under this specific heading in the overall references section which is accessible from the top bar of the guide.

Additional resources

Whenever possible, as we have just seen above, links are given throughout the guide to practical examples and to the findings of parallel projects on the area being discussed. The guide is complemented by a broader discussion paper on the key insights generated during the Fellowship in both its workshops and in the meetings with key higher education players from around the world. The Key Insights paper sets the broader context for the practical implementation suggestions outlined in the guide.

A video produced for the 2015 HERDSA conference on the Fellowship that discusses the key points made in the guide is also available at: http://youtu.be/26d0WrG1nf8

Acknowledgements

The design and delivery of the Fellowship’s capacity-building workshops and the development of this guide has indeed been a fine team effort.

I would like to acknowledge the senior leaders in the universities and colleges within and beyond Australia who hosted the workshops and supported their delivery; the 3700 academic leaders who participated in the workshops and were so generous in their feedback, sharing of successful practice and suggestions for enhancement of the guide; and the Office for Learning and Teaching and the Australian Government for supporting the Senior Fellowship.

Most importantly, I would like to thank the staff and leaders of Western Sydney University for their generous support of this work. My particular thanks go to Jane Box whose day-to-day support and generous assistance was invaluable and to Natalie McLaughlin, Luke McCallum and the team from Cyberdesign Works and the Western Sydney University web services team who helped develop the online guide.

The views expressed in the Fellowship, grant activities, this website and in the other materials produced do not necessarily reflect the views of the Office for Learning and Teaching or the sponsoring institutions.